Currently Empty: $0

Companies can’t stop overworking

Summary:

Research suggests all of this excess work isn’t good for anyone, employers included. So why are so many companies still encouraging it? And when companies do claim they are trying to reduce long hours, why do these efforts so often fail to make a difference?

By Corinne Purtill

That was David Solomon’s response to complaints of grueling working conditions for junior analysts at Goldman Sachs — in 2013. (The bank’s current CEO was then Goldman’s co-head of investment banking.) Shortly thereafter, the bank announced a “Saturday rule” forbidding most work from 9 p.m. Friday to 9 a.m. Sunday.

Eight years later, there’s a Groundhog Day quality to the discussions about burnout and long hours, prompted by a group of first-year analysts at Goldman who described “inhumane” labor conditions involving 100-hour workweeks.

Goldman’s “Saturday rule” is technically still on the books, but it’s flouted as much as it’s observed. Enforcing it more diligently was one of the actions Solomon pledged to take last month.

Overwork and burnout aren’t just issues at investment banks. For many, the pandemic has essentially erased the boundaries between work and home: White-collar workers feel stretched to their breaking point. And when offices reopen in earnest, few expect overwork to vanish or burnout to be relegated to the past.

Research suggests all of this excess work isn’t good for anyone, employers included. So why are so many companies still encouraging it? And when companies do claim they are trying to reduce long hours, why do these efforts so often fail to make a difference?

The Diminishing Returns of Overwork

“There is now a mountain of careful research showing that people who experience long hours of work have serious health consequences,” said John Pencavel, professor emeritus of economics at Stanford and author of “Diminishing Returns at Work: The Consequences of Long Working Hours.”

A review of more than 200 studies over two decades on the relationship between long work hours and health found a correlation between extended workweeks and a higher incidence of heart problems and high blood pressure. People who worked longer hours (which in most studies meant 50 to 60 hours a week — practically part time by some industry standards) were more likely to suffer injuries on the job and poor sleep at home. There was also a strong link between long work hours and behaviors — such as smoking, and the use of alcohol and substances — that end up affecting workers’ health.

It’s not only employees’ health that suffers when regularly working long hours. It’s also their work. Research has suggested that relationships between rest and problem-solving ability, between time away from work and some aspects of job performance, and between sleep deprivation and lower cognitive performance.

An eye-opening study by Pencavel explored how long hours affect work output by examining detailed data about munitions plant workers during World War I, who, like today’s invest bankers, often worked 70 to 90 hours a week. (The importance of their work, or at least the danger of it, is hard to compare with editing slide decks at an investment bank, but white-collar work is hard to quantify in a similar way.)

For the first 49 hours of the week, there was a direct relationship between time and productivity — the more employees worked, the more they got done. Starting at hour 50, employees still produced more the more they worked, but the output for each additional hour worked started to shrink. And after about 64 hours, productivity collapsed — there was little to show for all that extra time except for a lot of additional on-the-job injuries. Pencavel also found that workers who worked seven consecutive days without rest produced less than people who worked the same number of hours over six days in a week.

There’s no magic number of hours at which returns diminish that applies to all workers and all industries, he said. But research doesn’t support the idea that extreme work schedules directly translate to extraordinary productivity.

Why Efforts to Reduce Overwork Fail

Even in demanding fields, companies have had some success with models that produce high volumes of quality work without decimating employee health and engagement.

Over the past decade, Boston Consulting Group and London-based PwC, the brand name for PricewaterhouseCoopers, have both rolled out flexibility policies that allow for greater work-life balance, in large part thanks to demands from younger workers. PwC granted all employees the right to ask for flexible work schedules, and this past week announced it will pay a $250 bonus, up to four times a year, to employees who take a full consecutive week of vacation. Boston Consulting introduced options for employees to take up to two months off or reduce their work schedules while remaining on their career tracks. The gradual return to the office also offers employers an opportunity to experiment with flexible schedules.

Organizations can change. Their people are often better off when they do. But they have to actually want to do so. And when it comes to ultracompetitive firms such as Goldman, and the people who choose to work there, the incentive to change may simply not be there.

That’s the conclusion that Alexandra Michel has reached after two decades observing investment bankers, both in the depths of analyst hell and, for those who eventually leave, in their post-banking lives. Michel, an adjunct professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education, also worked at Goldman for five years — three as an analyst and two in the chief of staff’s office — before leaving to get her doctorate at Wharton.

Michel has been following four cohorts of investment bankers for the past 20 years. She has documented a business model that relies on inexhaustible waves of new talent. Most workers endure grueling working hours, and around the fourth year on the job, many analysts start seeing their bodies break down. Yet after countless hours interviewing current and former bankers, she believes that discussions of flexibility and work-life balance are moot in a culture that values the process of competition at least as much as the actual result.

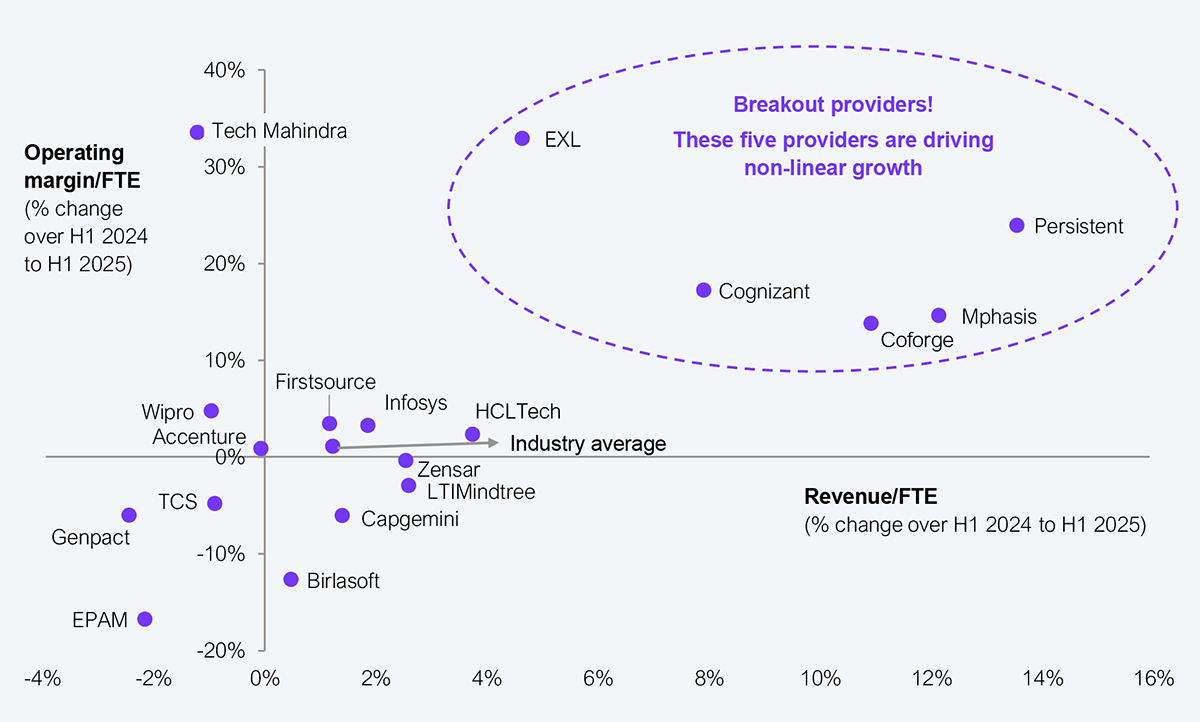

Source: GWFM Research

Subscribe as a member: https://globalwfm.com/become-gwfm-member/

Visit us for WFM Learning Academy: https://gwfmlearning.online/courses/